PHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS LINKING RESISTANCE EXERCISE TO BODY COMPOSITION AND ENERGY EXPENDITURE

Educational Research Overview

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

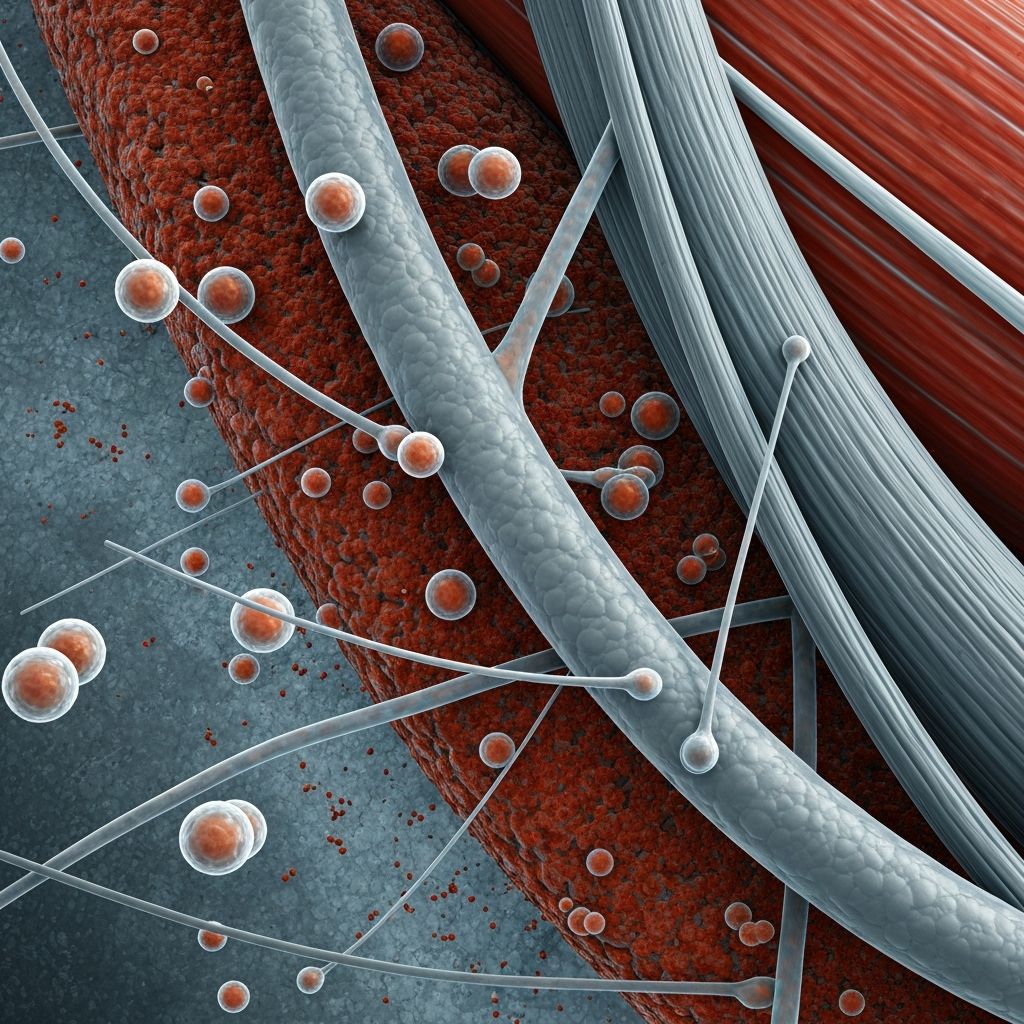

Skeletal Muscle and Resting Metabolic Rate

Research on body composition demonstrates that skeletal muscle tissue contributes significantly to resting metabolic rate (RMR). Cross-sectional studies comparing individuals with different muscle mass levels show consistent associations between lean mass and daily energy expenditure at rest. Longitudinal intervention trials examining changes in body composition over time have documented that increases in muscle mass correlate with measurable increases in RMR, though the effect size varies across populations and measurement methodologies. These observations form the physiological foundation for understanding how resistance exercise adaptations may influence overall energy balance through changes in metabolic rate.

The relationship between muscle mass and RMR is not linear and depends on several factors including age, sex, training history, and genetic predisposition. Public health guidance in the United Kingdom, including the UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines, acknowledges the role of muscle tissue in metabolic health as part of broader physical activity recommendations, though without prescriptive guidance on resistance modality specifically.

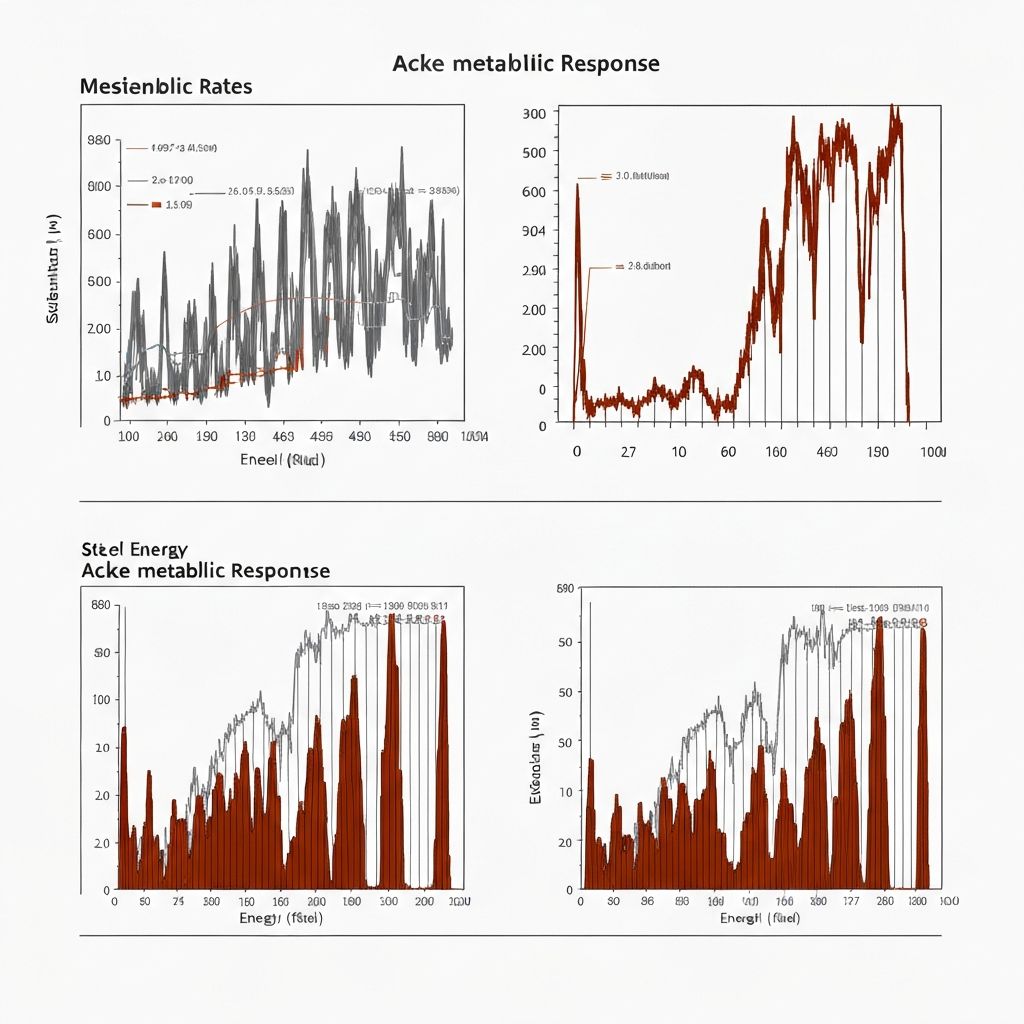

Acute Energy Expenditure During and After Resistance Exercise

Controlled laboratory trials examining acute metabolic responses to resistance exercise have documented several energy expenditure phenomena. The term "excess post-exercise oxygen consumption" (EPOC) refers to elevated metabolic rate in the recovery period following exercise. Research protocols measuring oxygen consumption and energy substrate utilization during and after resistance sessions show that the magnitude and duration of EPOC varies depending on exercise intensity, volume, rest intervals, and individual characteristics.

Acute substrate oxidation studies reveal that resistance exercise typically utilizes both carbohydrate and fat sources, with relative contribution influenced by intensity and training status. These acute metabolic perturbations are distinct from chronic adaptations and represent single-session responses documented under laboratory conditions.

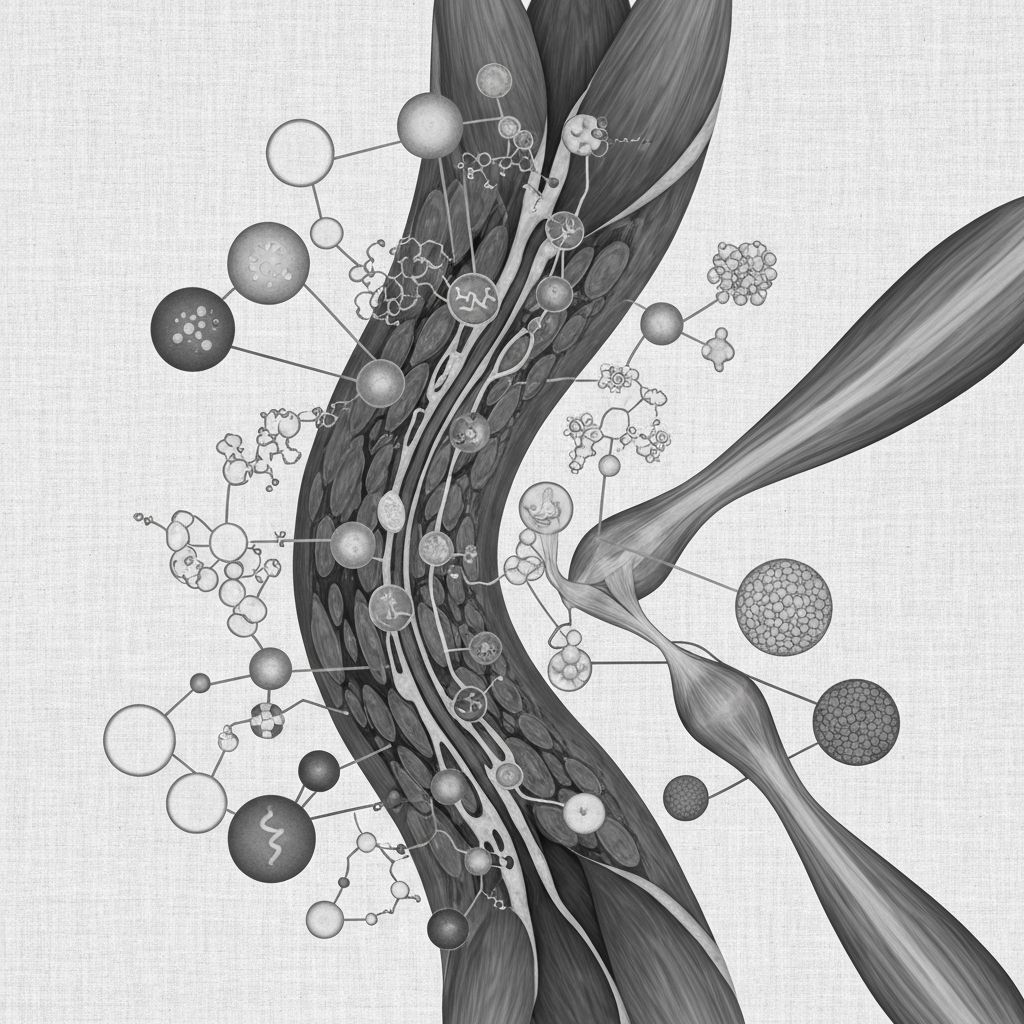

Chronic Adaptations in Lean Mass

Intervention studies tracking changes in body composition over weeks to years consistently document increases in lean mass (skeletal muscle) in response to progressive resistance training across diverse populations including younger adults, middle-aged, and older individuals. These chronic adaptations are measured using techniques such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). The magnitude of lean mass gain varies considerably based on training variables (intensity, frequency, duration), nutritional status, age, sex, and baseline characteristics.

Histological research on muscle tissue demonstrates that increased muscle mass results from both hypertrophy (increase in muscle fiber size) and, in some populations, hyperplasia (increase in fiber number). The molecular signalling pathways involved in these adaptations include mechanotransduction, protein synthesis regulation, and hormonal influences. These adaptations represent well-documented physiological responses to repeated mechanical loading of muscle tissue.

It is important to note that while lean mass gains are consistently observed, the relationship between these changes and other outcome variables (such as total body weight or body composition distribution) depends on broader lifestyle context including total energy intake and total physical activity patterns.

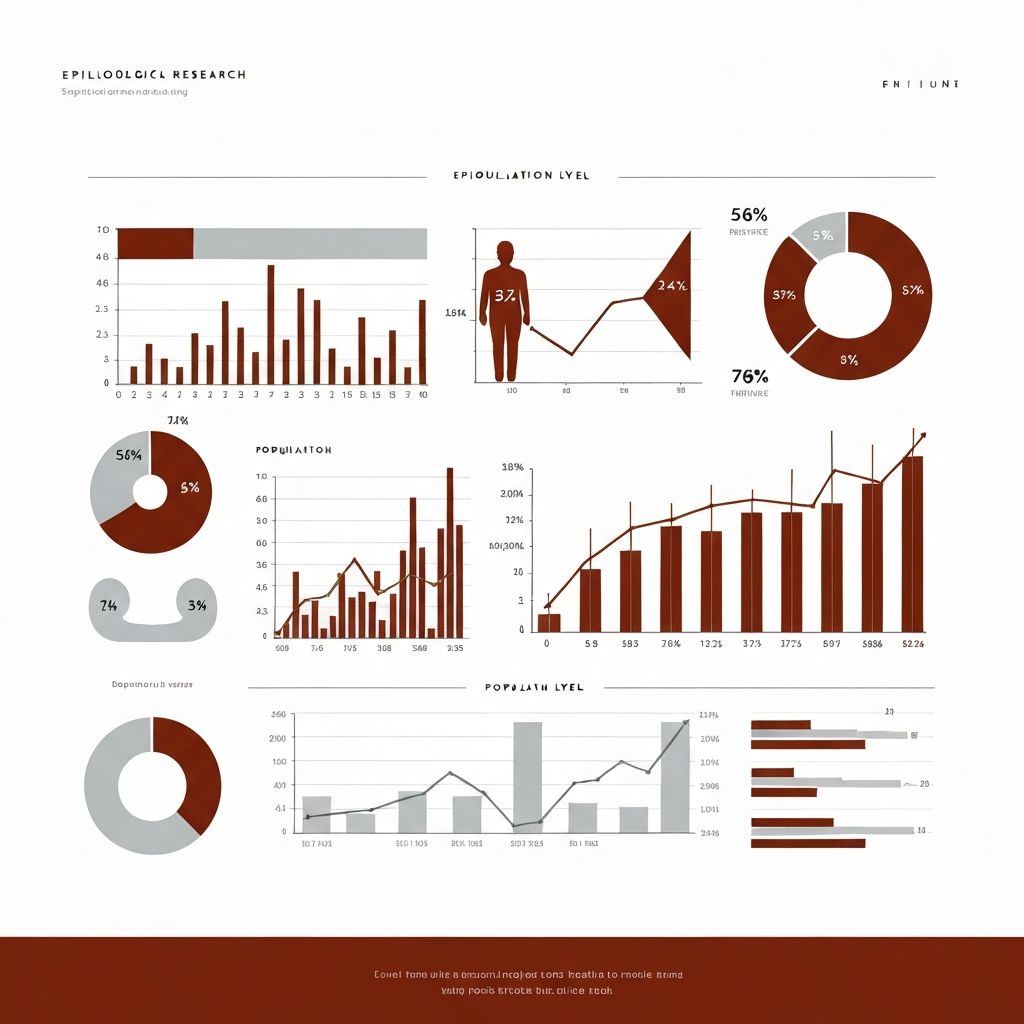

Population-Level Associations Between Muscularity and Energy Balance

Observational cohort studies examining thousands of individuals have documented associations between higher levels of muscularity (measured via lean mass indices, muscle circumference, or strength metrics) and more favorable long-term energy balance outcomes. These associations are observed across age groups and sexes, though effect sizes and patterns vary.

It is critical to interpret these associations within their proper epidemiological context. Correlation does not imply causation, and higher muscle mass is often accompanied by other lifestyle factors (dietary patterns, total physical activity, sleep quality) that independently influence energy balance. Population-level data cannot isolate the specific contribution of resistance exercise or muscle mass alone without accounting for confounding variables.

Resistance vs. Aerobic Modality Comparison

| Characteristic | Resistance Exercise | Aerobic Exercise |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Energy Expenditure | Lower during session; longer EPOC duration | Higher during session; shorter EPOC |

| Primary Lean Mass Change | Increase in skeletal muscle mass | Minimal change; possible slight decrease |

| Substrate Utilization | Mixed carbohydrate/fat oxidation | Higher fat oxidation at moderate intensity |

| Chronic Metabolic Adaptation | Increased RMR via muscle mass gain | Minimal RMR change |

| Cardiovascular Response | Intermittent demand; variable heart rate | Sustained cardiovascular demand |

Comparative research demonstrates that resistance and aerobic exercise modalities produce distinct energy expenditure profiles both acutely and chronically. The choice of modality influences the pattern of energy cost, substrate utilization, and physiological adaptations. Both modalities contribute to overall energy balance through different mechanisms, and the optimal approach depends on individual goals, capacity, and total activity context.

Resistance Exercise in UK Physical Activity Guidelines

The UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines recommend muscle-strengthening activities at least twice per week for adults as part of a comprehensive physical activity approach. These guidelines position resistance exercise within a broader framework of total physical activity, acknowledging its distinct physiological benefits including maintenance of skeletal muscle mass, bone health, and metabolic function.

The guidelines do not prescribe resistance exercise specifically for energy balance or weight management. Instead, resistance is presented as a component of holistic physical activity recommendations that support long-term health maintenance across multiple physiological systems. This public health perspective recognizes the role of muscle tissue in metabolic and musculoskeletal health without making promises regarding specific body composition outcomes.

Individual Variability in Response

Research demonstrates substantial variability in how individuals respond to resistance training and exercise in general. Genetic factors significantly influence muscle growth potential, baseline metabolic rate, and capacity for endurance adaptations. Age affects the rate of adaptation and the magnitude of lean mass gains, with older adults typically showing slower responses. Training status plays a critical role: individuals new to resistance training typically experience larger initial lean mass gains than highly trained individuals. Sex differences in hormonal profiles, particularly androgens and estrogens, influence muscle adaptation rates and patterns.

Nutritional status, particularly dietary protein intake and overall energy balance, modulates the physiological response to training stimulus. Sleep quality, stress levels, and recovery practices affect adaptation processes. These contextual factors explain why population averages in research studies conceal considerable individual heterogeneity. Observations of average effects in controlled trials cannot predict individual responses, highlighting the importance of professional guidance for personal activity decisions.

This variability underscores why educational information about group-level physiological mechanisms cannot substitute for individualized assessment by qualified healthcare or exercise professionals.

Methodological Considerations in Research

Understanding the limitations of current research is essential for properly interpreting findings on resistance exercise and energy expenditure. Many acute studies occur in highly controlled laboratory conditions that may not reflect real-world environments. Measurement precision in body composition analysis has inherent error margins, particularly at smaller magnitudes of change.

Intervention studies typically face challenges in controlling for confounding variables such as dietary adherence, compliance with exercise prescription, and concurrent lifestyle changes. The duration of many trials (8–12 weeks) captures acute adaptations but may not reflect long-term homeostatic adjustments. Publication bias may preferentially highlight positive findings, potentially overestimating effect sizes in practice.

Differences in study quality, participant populations, and outcome measurement methodologies create heterogeneity in the literature, requiring careful critical appraisal of individual studies and synthesis through systematic review frameworks.

Total Physical Activity Context

The physiological effects of resistance exercise on body composition and energy expenditure cannot be meaningfully interpreted in isolation. Total energy expenditure comprises basal metabolic rate, activity energy expenditure (from all forms of movement), and the thermic effect of food. Changes in one modality of exercise must be viewed within the context of total physical activity levels.

Research examining comprehensive activity patterns demonstrates that individuals who change one form of exercise sometimes unconsciously compensate by altering other activity or dietary behaviours. Long-term energy balance outcomes depend on sustained patterns across all these components, not on optimizing a single modality.

This systemic perspective aligns with public health guidance that emphasizes total activity across the week rather than prescribing specific exercise formats. Understanding resistance exercise mechanisms enriches knowledge about how the body responds to physical stress, but does not constitute personalized activity guidance.

Blog Articles

Muscle Mass and Resting Metabolic Rate in Research

Examination of the relationship between lean tissue and daily energy expenditure from longitudinal trials and cross-sectional studies.

Read More →

Acute Energy Expenditure After Resistance Sessions

Overview of EPOC, substrate oxidation, and metabolic responses documented in controlled laboratory trials.

Read More →

Hypertrophy Adaptations in Intervention Studies

Chronic changes in muscle fiber size and lean mass observed across diverse populations over training periods.

Read More →

Resistance vs Aerobic: Comparative Physiology

Energy expenditure profiles, adaptations, and physiological distinctions between resistance and aerobic modalities.

Read More →

Muscularity and Long-Term Weight Stability

Population-level associations between muscle mass indices and energy balance outcomes in observational cohorts.

Read More →

Limitations in Resistance Exercise Research

Methodological considerations, confounders, measurement challenges, and critical interpretation of study findings.

Read More →Explore More on Exercise Physiology

VIEW ALL ARTICLESFrequently Asked Questions

Research demonstrates that skeletal muscle contributes measurably to resting metabolic rate. Cross-sectional studies comparing individuals with different body composition profiles, and longitudinal intervention trials measuring changes in muscle mass over time, show consistent associations between lean tissue and daily energy expenditure at rest. However, the effect size varies considerably across populations, measurement methods, and individual characteristics. Muscle tissue accounts for a portion of RMR variation, but other factors including organ mass, thyroid function, and genetic differences also influence overall metabolic rate.

Excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC) refers to elevated oxygen uptake and metabolic rate in the recovery period following exercise cessation. Laboratory studies measuring oxygen consumption after resistance sessions document measurable EPOC lasting hours. The magnitude and duration vary with exercise intensity, session volume, rest interval structure, and individual characteristics. EPOC contributes to acute post-exercise energy expenditure but represents only a portion of total daily energy balance. The effect size of EPOC is smaller than often portrayed in popular literature, and the practical significance depends on total weekly activity volume and dietary context.

Intervention studies document substantial variability in lean mass gains in response to resistance training. Many studies report gains ranging from 1–3 kg over 8–12 week periods, though larger gains are observed in some populations and shorter timeframes in others. Factors influencing magnitude include training experience (novices typically gain more rapidly than trained individuals), age (younger populations often respond faster), sex (testosterone levels influence response rate), nutritional status, genetics, and training variables. Population-level averages conceal individual variation; some individuals experience minimal gain despite adherence, while others gain substantially. Long-term studies suggest gains continue but at slower rates beyond initial adaptation phases.

Resistance exercise applies mechanical stress to muscle fibers, triggering mechanotransduction pathways that activate protein synthesis signalling. Key regulatory pathways include the mTOR pathway, involving both mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades. Mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress associated with resistance exercise all contribute to activation of these pathways. The resulting increase in protein synthesis rates (particularly of contractile proteins actin and myosin) and modest changes in protein breakdown collectively lead to net protein accretion and increase in muscle fiber cross-sectional area. Hormonal factors including insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and androgens modulate the magnitude of these responses. Complete understanding of all molecular mechanisms remains an active area of research.

Resistance and aerobic exercise produce distinct acute and chronic physiological responses. Acute energy expenditure during resistance sessions is typically lower than aerobic activity, but EPOC duration is longer. Substrate utilization patterns differ: resistance typically uses mixed carbohydrate and fat sources, while moderate-intensity aerobic work favors fat oxidation. Chronic adaptations differ substantially: resistance training primarily increases skeletal muscle mass, while aerobic training improves cardiovascular fitness with minimal lean mass change. Cardiovascular demand patterns differ: resistance involves intermittent peak demand with recovery periods, while aerobic is sustained. Both modalities contribute to overall energy balance through different mechanisms. The physiological superiority of either modality depends entirely on the specific health or fitness outcome being considered.

Population-level observational studies examine associations between variables in large groups but cannot isolate cause-and-effect relationships. Controlled intervention trials randomly assign participants and measure specific outcomes, allowing better determination of causality. Population studies reveal patterns and associations (e.g., higher muscle mass is associated with more stable weight over time) but cannot confirm that the association is causal. Confounding variables—unmeasured or inadequately controlled factors—may explain the association. Intervention studies have superior internal validity for causality but typically involve smaller samples and shorter timeframes. Both approaches contribute to evidence; observational data generates hypotheses and provides real-world context, while experiments test mechanisms. The complete evidence picture requires considering both types of research.

Research documents substantial individual variation in response to identical resistance training protocols. Genetic factors significantly influence muscle growth capacity, baseline metabolic rate, and fibre type distribution. Age affects adaptation rates: older adults typically show slower responses. Hormonal profiles, particularly androgens and estrogens, influence response magnitude. Training history matters: novices typically respond more robustly than highly trained individuals (initial rapid adaptation followed by plateau). Nutritional status, particularly protein intake and total energy balance, modulates response. Sleep quality, stress levels, recovery practices, and overall lifestyle factors all influence adaptation. These contextual factors explain why population averages in research studies conceal considerable individual heterogeneity. This variability underscores why group-level research findings cannot predict individual responses and why professional guidance matters for personal decisions.

No. This website provides general educational information about physiological mechanisms observed in research contexts. It is designed to explain how scientists study exercise physiology, what the research literature documents, and what mechanisms appear involved. Educational information about group-level mechanisms cannot substitute for individualized assessment. Personal exercise decisions should be made with guidance from qualified healthcare professionals or certified exercise specialists who can assess individual circumstances, capacity, health status, goals, and preferences. The individual variability documented throughout this site means that general information does not predict personal outcomes. This distinction between educational explanation and personal guidance is fundamental to the purpose of this resource.